The aim of nonlinear fitting is to estimate the parameter values which best describe the data. Generally we can describe the process of nonlinear curve fitting as below.

Origin provides options of different algorithm, which have different iterative procedure and statistics to define minimum distance.

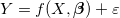

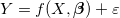

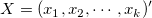

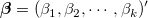

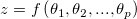

A general nonlinear model can be expressed as follows:

|

(1) |

where  is the independent variables and

is the independent variables and  is the parameters.

is the parameters.

Examples of the Explicit Function |

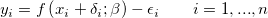

The least square algorithm is to choose the parameters that would minimize the deviations of the theoretical curve(s) from the experimental points. This method is also called chi-square minimization, defined as follows:

![\chi ^2=\sum_{i=1}^n \left [ \frac{Y_i-f(x_i^{\prime },\hat{\beta }) } {\sigma _i} \right ]^2 \chi ^2=\sum_{i=1}^n \left [ \frac{Y_i-f(x_i^{\prime },\hat{\beta }) } {\sigma _i} \right ]^2](../images/Theory_of_Nonlinear_Curve_Fitting/math-06e0bc4dd4c9e79eae6f116e751e9eb5.png?v=0)

|

(2) |

where  is the row vector for the ith (i = 1, 2, ... , n) observation.

is the row vector for the ith (i = 1, 2, ... , n) observation.

The figure below illustrates the concept to a simple linear model (Note that multiple regression and nonlinear fitting are similar). The Best-Fit Curve represents the assumed theoretical model. For a particular point If there are two independent variables in the regression model, the least square estimation will minimize the deviation of experimental data points to the best fitted surface. When there are more then 3 independent variables, the fitted model will be a hypersurface. In this case, the fitted surface (or curve) will not be plotted when regression is performed. |

Origin provides two options to adjust the parameter values in the iterative procedure

The Levenberg-Marquardt (L-M) algorithm11 is a iterative procedure which combines the Gauss-Newton method and the steepest descent method. The algorithm works well for most cases and become the standard of nonlinear least square routines.

value from the given initial values:

value from the given initial values:  .

. , say

, say  = 0.001

= 0.001 and evaluate

and evaluate

,increase

,increase  by a factor of 10 and go back to step 3

by a factor of 10 and go back to step 3 , decrease

, decrease  by a factor of 10, update the parameter values to be

by a factor of 10, update the parameter values to be  and go back to step 3

and go back to step 3Besides the L-M method, Origin also provides a Downhill Simplex approximation9,10. In geometry, a simplex is a polytope of N + 1 vertices in N dimensions. In non-linear optimization, an analog exists for an objective function of N variables. During the iterations, the Simplex algorithm (also known as Nelder-Mead) adjusts the parameter "simplex" until it converges to a local minimum.

Different from L-M method, the Simplex method does not require derivatives, and it is effective when the computational burden is small. Normally, if you did not get a good value for parameter initialization, you can try this method to get the approximate parameter value for further fitting calculations with L-M. The Simplex method tends to be more stable in that it is less likely to wander into a meaningless part of the parameter space; on the other hand, it is generally much slower than L-M, especially very close to a local minimum. Actually, there is no "perfect" algorithm for nonlinear fitting, and many things may affect the result (e.g., initial values). In complicated models, you may find one method may do better than the other. Additionally, you may want to try both methods to perform the fitting operation.

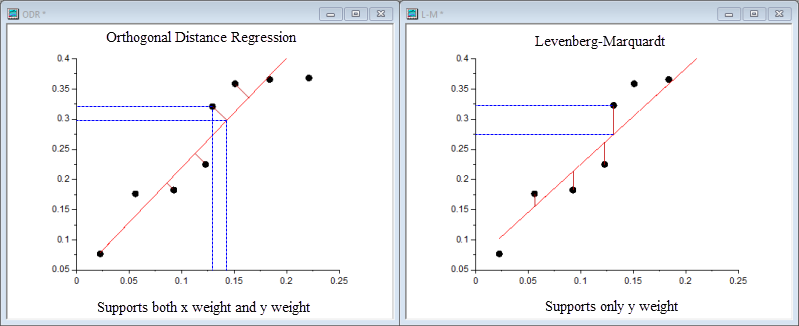

The Orthogonal Distance Regression (ODR) algorithm minimizes the residual sum of squares by adjusting both fitting parameters and values of the independent variable in the iterative process. The residual in ODR is not the difference between the observed value and the predicted value for the dependent variable, but the orthogonal distance from the data to the fitted curve.

Origin uses the ODR algorithm in ODRPACK958.

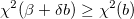

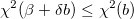

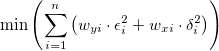

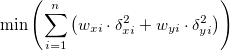

For a explict function, the ODR algorithm could be expressed as:

subject to the constraints:

where  and

and  are the user input weights of

are the user input weights of  and

and  ,

,  and

and  are the residual of the corresponding

are the residual of the corresponding  and

and  , and

, and  is the fitting parameter.

is the fitting parameter.

For more details of the ODR algorithm, please refer to ODRPACK958.

To choose the ODR or L-M algorithm for your fitting, you may refer to the following table for information:

| Orthogonal Distance Regression | Levenberg-Marquardt | |

|---|---|---|

| Application | Both implicit and explicit functions | Only explicit functions |

| Weight | Support both x weight and y weight | Support only y weight |

| Residual Source | The orthogonal distance from the data to the fitted curve | The difference between the observed value and the predicted value |

| Iteration Process | Adjusting the values of fitting parameters and independent variables | Adjusting the values of fitting parameters |

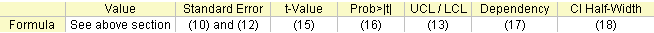

A general implicit function could be expressed as:

|

(5) |

where  and

and  are the variables,

are the variables,  are the fitting parameters and

are the fitting parameters and  is a constant.

is a constant.

Examples of the Implicit Function:

|

The ODR method can be used for both implicit functions and explicit functions. To learn more details of ODR method, please refer to the description of ODR mehtod in above section

For implicit functions, the ODR algorithm could be expressed as:

subject to:

where  and

and  are the user input weights of

are the user input weights of  and

and  ,

,  and

and  are the residual of the corresponding

are the residual of the corresponding  and

and  , and

, and  is the fitting parameter.

is the fitting parameter.

When the measurement errors are unknown,  are set to 1 for all i, and the curve fitting is performed without weighting. However, when the experimental errors are known, we can treat these errors as weights and use weighted fitting. In this case, the chi-square can be written as:

are set to 1 for all i, and the curve fitting is performed without weighting. However, when the experimental errors are known, we can treat these errors as weights and use weighted fitting. In this case, the chi-square can be written as:

|

|

(6) |

There are a number of weighting methods available in Origin. Please read Fitting with Errors and Weighting in the Origin Help file for more details.

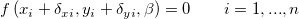

The fit-related formulas are summarized here:

Computing the fitted values in nonlinear regression is an iterative procedure. You can read a brief introduction in the above section (How Origin Fits the Curve), or see the below-referenced material for more detailed information.

During L-M iteration, we need to calculate the partial derivatives matrix F, whose element in ith row and jth column is:

|

|

(7) |

where  is the error of y for the ith observation if Instrumental weight is used. If there is no weight,

is the error of y for the ith observation if Instrumental weight is used. If there is no weight,  . And

. And  is evaluated for each observation

is evaluated for each observation  in each iteration.

in each iteration.

Then we can get the Variance-Covariance Matrix for parameters ![]() by:

by:

|

|

(8) |

where  is the transpose of the F matrix, s2 is the mean residual variance, also called Reduced Chi-Sqr, or the Deviation of the Model, and can be calculated as follows:

is the transpose of the F matrix, s2 is the mean residual variance, also called Reduced Chi-Sqr, or the Deviation of the Model, and can be calculated as follows:

|

|

(9) |

where n is the number of points, and p is the number of parameters.

The square root of the main diagonal value of this matrix C is the Standard Error of the corresponding parameter

|

|

(10) |

where Cii is the element in ith row and ith column of the matrix C. Cij is the covariance between θi and θj.

You can choose whether to exclude s2 when calculating the covariance matrix. This will affect the Standard Error values. When excluding s2, clear the Use reduce Chi-Sqr check box on the Advanced page under Fit Control panel. The covariance is then calculated by:

|

|

(11) |

So the Standard Error now becomes:

|

|

(12) |

The parameter standard errors can give us an idea of the precision of the fitted values. Typically, the magnitude of the standard error values should be lower than the fitted values. If the standard error values are much greater than the fitted values, the fitting model may be overparameterized.

Origin estimates the standard errors for the derived parameters according to the Error Propagation formula, which is an approximate formula.

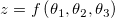

Let  be the function with a combination (linear or non-linear) of

be the function with a combination (linear or non-linear) of  variables

variables  .

.

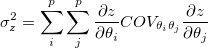

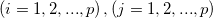

The general law of error propagation is:

where  is the covariance value for

is the covariance value for  , and

, and  .

.

You can choose whether to exclude mean residual variance  when calculating the covariance matrix

when calculating the covariance matrix  , which affects the Standard Error values for derived parameters. When excluding

, which affects the Standard Error values for derived parameters. When excluding  , clear the Use reduce Chi-Sqr check box on the Advanced page under Fit Control panel.

, clear the Use reduce Chi-Sqr check box on the Advanced page under Fit Control panel.

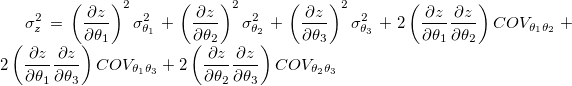

For example, using three variables

we get:

Now, let the derived parameter be  , and let the fitting parameters be

, and let the fitting parameters be  . The standard error for the derived parameter

. The standard error for the derived parameter  is

is  .

.

Origin provides two methods to calculate the confidence intervals for parameters: Asymptotic-Symmetry method and Model-Comparison method.

One assumption in regression analysis is that data is normally distributed, so we can use the standard error values to construct the Parameter Confidence Intervals. For a given significance level, α, the (1-α)x100% confidence interval for the parameter is:

|

|

(13) |

The parameter confidence interval indicates how likely the interval is to contain the true value.

The confidence interval illustrated above is Asymptotic, which is the most frequently used method to calculate the confidence interval. The "Asymptotic" here means it is an approximate value.

If you need more accurate values, you can use the Model Comparison Based method to estimate the confidence interval.

If the Model Comparison method is used, the upper and lower confidence limits will be calculated by searching for the values of each parameter p that makes RSS(θj) (minimized over the remaining parameters) greater than RSS by a factor of (1+F/(n-p)).

|

|

(14) |

where F = Ftable(α,1,n-p)and RSS is the minimum residual sum of square found during the fitting session.

You can choose to perform a t-test on each parameter to see whether its value is equal to 0. The null hypothesis of the t-test on the jth parameter is:

|

And the alternative hypothesis is:

|

The t-value can be computed as:

|

|

(15) |

The probability that H0 in the t test above is true.

|

|

(16) |

where tcdf(t, df) computes the lower tail probability for Student's t distribution with df degree of freedom.

If the equation is overparameterized, there will be mutual dependency between parameters. The dependency for the ith parameter is defined as:

|

|

(17) |

and (C-1)ii is the (i, i)th diagonal element of the inverse of matrix C. If this value is close to 1, there is strong dependency.

To learn more about how the value assess the quality of a fit model, see Model Diagnosis Using Dependency Values page

The Confidence Interval Half Width is:

|

|

(18) |

where UCL and LCL is the Upper Confidence Interval and Lower Confidence Interval, respectively.

Several fit statistics formulas are summarized below:

The Error degree of freedom. Please refer to the ANOVA Table for more details.

The residual sum of squares:

|

|

(19) |

The Reduced Chi-square value, which equals the residual sum of square divided by the degree of freedom.

|

|

(20) |

The R2 value shows the goodness of a fit, and can be computed by:

|

|

(21) |

where TSS is the total sum of square, and RSS is the residual sum of square.

The adjusted R2 value:

|

|

(22) |

The R value is the square root of R2:

|

|

(23) |

For more information on R2, adjusted R2 and R, please see Goodness of Fit.

Root mean square of the error, or the Standard Deviation of the residuals, equal to the square root of reduced χ2:

|

|

(24) |

The ANOVA Table:

Note: The ANOVA table is not available for implicit function fitting.

| df | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Value | Prob > F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model |

p |

SSreg = TSS - RSS |

MSreg = SSreg / p |

MSreg / MSE |

p-value |

| Error |

n - p |

RSS |

MSE = RSS / (n - p) |

||

| Uncorrected Total |

n |

TSS |

|||

| Corrected Total |

n-1 |

TSScorrected |

Note: In nonlinear fitting, Origin outputs both corrected and uncorrected total sum of squares: Corrected model:

|

|

(25) |

Uncorrected model:

|

|

(26) |

The F value here is a test of whether the fitting model differs significantly from the model y=constant. Additionally, the p-value, or significance level, is reported with an F-test. We can reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than  , which means that the fitting model differs significantly from the model y=constant.

, which means that the fitting model differs significantly from the model y=constant.

The confidence interval for the fitting function says how good your estimate of the value of the fitting function is at particular values of the independent variables. You can claim with 100α% confidence that the correct value for the fitting function lies within the confidence interval, where α is the desired level of confidence. This defined confidence interval for the fitting function is computed as:

|

|

(27) |

where:

|

|

(28) |

The prediction interval for the desired confidence level α is the interval within which 100α% of all the experimental points in a series of repeated measurements are expected to fall at particular values of the independent variables. This defined prediction interval for the fitting function is computed as:

|

|

(29) |

where

is Reduced

is Reduced

| Notes: The Confidence Band and Prediction Band in the fitted curve plot are not available for implicit function fitting. |